Chandra Prasad Pokhrel

Central Department of Botany, IOST, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal

Lal Bahadur Thapa

Central Department of Botany, IOST, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal

Chandra Mohan Gurmachhan

Plant Research Center, Department of Plant Resource, GoN, Jumla, Nepal

Abstract

Kali Marshi is one of the high valuable highland rice landraces natively found in Jumla. The aim of this study is to know the cultivation practices and associated traditional knowledge. The study was conducted in Chhumchoure Ward no3of Patarashi Municipality located at 2850 masl, Jumla district, Nepal. A household survey was conducted using stratified random sampling techniques. A set of questionnaires, visual observations including focus group discussion, and key informant interviews were applied for data collection. The household size of the study area was 5.61±1.63 and the paddy landholding size was 5.72 ± 4.54 Ropani (1 Ropani=508.5 m2). Only 31% of households in the study area have food sufficiency. Cultivation practices of the rice Kali Marshi start from seed soaking on the day 25th March. The practice has been found associated with date and timing of rice phenology which is not yet affected by the climate change events. The practices have now become an important culture. Work division based on gender, priority to the household owner, and community leadership to the leader (Mukhiya) are fund as the significant traditions. The productivity of rice is 18.5 t/ h, which is lower than that of national productivity. This documentation would facilitate in the promotion as well as help to promote Kali Marshi as Geographical Indicator.

Keywords

Jumli Marshi, Cultivation practices, Traditional knowledge, Harvesting, Geographical indicator.

1. Introduction

Rice is the most important food crop in the world that feeds the majority of the world’s population. In the Asian continents, Nepal is one of the centers of origin and diversity of Asian rice (CDD 2015; Chang 1976; Joshi 2005). The rice in Nepal is not only the main source of food and nutrition but also it has been associated with social and economic status of the people. It has contributed more than 50 and 30 percent of food grain and calorie requirements, respectively in Nepal (Dhungel, 2017).

There are over 2500 varieties of rice landraces including 50 aromatic landraces and 4 wild species in Nepal (CDD 2015; Mallick, 1981). Among them, CDD (2015) has listed 157 rice landraces that are under cultivation in Nepal. Rice in Nepal grows under diverse environmental conditions ranging from Terai (60 m) to foothills and the mountain at the elevation up to 3050 masl (Devkota 2017).

Jumla is one of the mountain districts of Karnali Province, Nepal ranks first in terms of area and production of rice (ADO 2013). The district is very well-known for the cultivation of highland rice, namely “Kali Marshi or Jumli Marshi”, a Japonica type of cold tolerant landraces. Having been its good taste and aroma with high nutritional value, its demand is mounting day by day among the urban dwellers. Chhumchaur and Gidikhola areas of Jumla are the major areas of cultivation of Kali Marshi.

The Government of Nepal and its line agencies are always seeking to introduce the high yielding rice varieties including high agriculture inputs but the importance of the landraces like Kali Marshi, traditional local knowledge associated with its cultivation, and socio-economic dimension are always overlooked. This led to jeopardize the high valued local rice landraces and traditional ecological knowledge of cultivation. Declining of the local landraces is associated with the loss of agriculture biodiversity (Newton et al. 2011) thereby threatening the local food security.

Moreover, a Geographical Indication (GI) is a collectively-owned, intellectual property rights (Ojha et al. 2020; Joshi and Gauchan 2020) that can ensure the farmers rights on traditional local knowledge of Kali Marshi and its cultivation practices is the best tool of rural development but yet to be practiced in Nepal. Considering the diverse value of rice Kali Marshi and the risk associated with its conservation, this study aims to document the traditional local/ecological knowledge and respective management practices influenced by various socio-cultural aspects of the Kali Marshi in Jumla.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Study Site:

Jumla is one of the remote and underdeveloped mountain districts of Nepal located in the Karnali Province. Sinja Valley of Jumla is the place where the Nepali language was originated. The district lies between 28.580 o N to 29.3070 o N and between 82.180o E to 88.120 o E, and covers the area of 2, 531 sq. km between an altitude range from 2000 m and 6424 masl at the summit of Patarasi Himal (the highest peak of the district) (Palikhey et al. 2016). The human development index is 0.409, per capita income index 0.385, adult literacy index 0.444, and life expectancy is 63.14 (GoN and UNDP 2014) of the district.

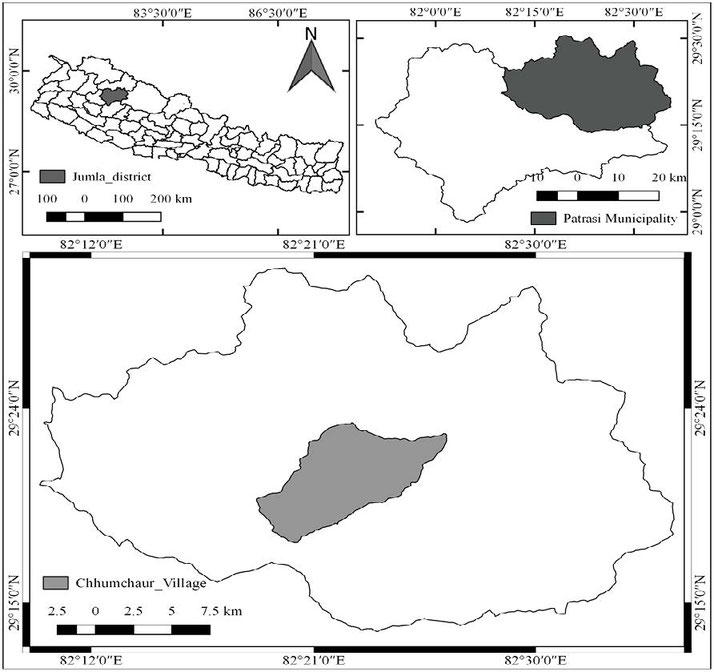

This study was conducted in the Chhumchaur village (2850 masl) of Patarashi Municipality, Ward no 3, Jumla, located at 29.335524° and 82.325314° E. (Fig 1). The village is located at the North East side of the district and about 15 Km away from the district headquarter Khalanga.

Fig. 1 Map of the study site

2.2 Research design and data collection

Both primary and secondary information were used for the study. Primary information was collected from household survey and field observation; and secondary information from local and national publications. A set of semi-structured questionnaires was prepared for the household survey. A stratified random sampling method was applied for the household survey (34 households). A focus group discussion was conducted and key informant interviews were also performed from representatives of socially acknowledged groups. Data compilation and entry was done using Microsoft Excel and analyzed. The survey was carried out in 2017and 2020.

3 Results and Discussion

3.1 Socio-economic profile

Of the 34 respondents, 70% were male and 30% were the female. Major caste of the study site was Chhetri (90.44%) followed by Tamange (7.72%), Bhote (0.02%) and rest were Untouchable/ Dalit and Bhramins. Average household size of Chhumchaur was 6.33 people (CBS 2014) and 5.61±1.63 was observed during the field study in 2020. The average size of landholding of the village was 12.67± 6.22 whereas the average size of rice landholding was 5.72 ± 4.54 Ropani (1 Ropani=508.5 m2). Only 31% of households of the study area have food sufficiency (Table 1).

Table 1. Family size, land holding size, rice productivity and food sufficiency of the study area

| Number of interviewed Farmers (M//F) | Family size | Total land holding size (Ropani) | Rice land holding size (Ropani) | Rice Productivity (t/h) | Food sufficiency (%) |

| 34(24/10) | 6.33 (CBS 2014) 5.61±1.63 (Field survey, 2017 and 2020) | 12.67± 6.22(1 Ropani= 508.5 m2 ) | 5.72 ± 4.54 | 1.8 |

Less than six months 13.79 Sufficient for six months 55.17 Sufficiency for one year 24.14 Food Surplus 6.89% |

3.2 Practices on Kali Marshi cultivation

3.2.1. Seed selection and seedling development

The study revealed that all the farmers themselves collect the healthy and good quality seeds of Kali Marshi either from the grain heaps (during the threshing) or directly from the panicle. The seeds are processed by removing dust materials and sundried and finally stored in special type of pot. The seed selection, processing, drying and storing activities are led by women.

According to the respondents, the rice seeds are soaked in water on the special day the March 25 (Chaitra 12 or 12/12 as per Nepalese calendar). The household head who is away from the home is mandatory to return his home by the date (March 25), otherwise, he is considered to be dead or he is in immense difficulty. This special date has not been changed by the local people for centuries. It signifies how the date and timing of the phenology of Kali Marshi have become a part of cultural practice. There are numerous studies related to climate change in Nepal and there are fluctuations of climatic events in the country (Aryal et al. 2020) but the special timing of Kali Marshi seed soaking is being changed.

The seedling development process is completed in two steps: germination at the house and seedling development in the field. The selected seeds are put either in any vessels or in jute bag for soaking in water for about one week. While soaking the seeds they change the fresh water regularly or directly the jute bag with seeds is left in nearby running stream. After soaking, the seeds are washed (some farmers use the salt for washing) by fresh water for 3-4 times and dry under the sun light for about one hour. Afterward, seeds are incubated / spread over the mat of jute or straw by covering it with Bhoj patra (Betula utilis), pine needle (Pinus spp.) or a woolen clothes; place nearby the cooking hearth (Photo 1).

After 3-4 days the seeds start to germinate and reaches about 1.5 cm (Photo - 2). These seedlings are then transferred to previously prepared puddle seedbed by April 4 (Chaitra 22). The Kasro (mix powder of two years old dung and burnt residue of firewood) is added to the nursery. The seedling can be ready for transplantation within 40-45 days after soaking. The practice of covering the spread seeds on Jute mat by B. utilia or pine needle or woolen cloth is for protection of temperature and moisture.

Photo 1. Use of Pine needle to cover the soaked seeds

Photo 2. Germinated seeds

3.2.2. Transplantation and harvesting

After harvesting of winter crops the land is ploughed twice with the help of bullocks by using a wooden plough. The puddle field for rice transplantation is prepared just few days earlier than rice plantation.

Mainly the males are involved in land preparation activities such as digging, plowing, puddling, and seedling transportation while females are involved in rice plantation and weeding. It indicates the practice of labour division during cultivation between males and females. Conducting the hard works are the responsibility of males.

According the informants, the irrigation is executed based on the local rules and regulations. The rules and regulations are set by community people which is basically for the turn of irrigation while there is limitation of irrigation water.

Generally, two manual weeding practices were prevalent. The use of chemical fertilizer and pesticides were not noticed during the study. Therefore, it can be expected that the fertility of the lands for Kali Marshi cultivation is not affected by chemical fertilizer and pesticides.

In the study area, rice harvesting activity is completed by the third week of October (Photo 3). The day to harvest is determined by the Mukhiya, a socially recognized elderly person of the village. This practice is also one of the remnants of ancient culture in the villages of Nepal. Harvesting is done manually by using sickle leaving 5-10 cm stubble. The harvested rice with panicles tied in bundles and brought to cleaned threshing floor or over the surface of clothes called Phara (made from wool). Again, men are involved in threshing whereas the women get involved in harvesting (cutting). The productivity of the rice was estimated 1.85 t./hector which is below the national productivity. The national productivity of rice is 3.7 t/h (MoALD, 2020).

The harvested rice-grains are cleaned by winnowing and hauled to home and dried appropriately. Once the

grains are dried, they are stored in a special pot made from wood or bamboo, or the clay pot or tranches. Rice straws are also transported and stored nearby

house yard as a heap and offered to livestock as feed. The size of rice straw heap is an indicator of the social status. Rice harvested field is open for livestock grazing until sowing of next winter crops. This practice is also useful as the livestocks defecate in the crop field which may reduce the amount of fertilization.

Photo 3. Crop ready for harvesting

All the farmers of study area were strongly shaped by subsistence and smallholders rice production in remote and fragile environments. Rice is traditionally grown (techniques and tools) once a year as the valuable crop and provides a major contribution to local food consumption and their livestock feed. There is an evidence of feminization in Agriculture.

Table 2. Crop Calendar of Kali Marshi in the study site

| Activities | Time Period | Responsible person | |

| Land Preparation |

Nursery: March first /Second week Paddy land: Puddling by the second week of May |

Male Male |

|

|

Seed Processing Seed Soaking and Germination |

Starts from March 17 to 25 Seed soaking for about 1 week; left for germination 3 to 4 days |

Female Female/ Male Male/female |

|

| Seedling Transplantation | By March 26- April 4 | Male and Female | |

| Seedling Transplantation | Started from second week of May and completed by the end of May | Female | |

| Weeding | June second week and July Second week (Twice) | Female | |

| Flowering | Named as “Kesar Khelne” in the beginning of September | ||

| Ripening | Second week of October | ||

| Harvesting | Completed by the third week of October | Cutting: female; Threshing and carrying the grains: Male |

Table 3: Characteristics of rice cultivation and use pattern of Kali Marshi

| Location | Rice crop/year; Land type | Cultivation practices and rice processing | Production type | Propose of rice | Major role of women in rice cultivation |

| Rural-mountain Chumchaure, Jumla, Nepal; | One; Traditional rice landscape; high social and economic status | Completely traditional tools; no mechanization; oxen for plowing; all manual work from plantation to rice milling; exchange of oxen and agricultural tools; Sufficient human resources within the family; in case of need traditional labor exchange-Perma; Special care for seed germination and nursery. | Subsistence; no use of fertilizer, pesticide and herbicide; Special manure-Karso for nursery, Farm Yard Manure for rice field; after rice land is used for cereals but most of the land is fellow; fellow use for livestock grazing . | Self-consumption; cultural and religious proposes; not sufficient; Sometime exchange with some domestic goods; Selling only in the time of financial need (for health or education); rice straw is the best livestock feed. | Seed selection, processing and storage; Seed prepare for soaking; transplantation of seedlings; weeding; harvesting of rice and processing (drying) and storage of rice |

The detail characteristics of rice cultivation and use pattern is presented in Table 3. The farmers from the study area were poorly equipped with modern technology along with excluded from access to technical support, information, credit, marketing and other services, which leads to poor productivity. The resource-poor farmers in the developing world like

Nepal are at the risk-prone and marginal environments remain untouched by modern agriculture technology (Alteri, 2002). The farmers in the study area were confronted with labor-intensive

and low productive of rice and lack of off-farm employment. Seasonal migration for employment and lucrative income from collecting and selling of medicinal and aromatic plants had an influence on rice cultivation.

4. Conclusions

Methods of seedling preparation, seedling transplantation and harvesting of Kali Marshi are the

unique practices among the community people of the study site. The practice has been found associated with date and timing of rice phenology which is not yet affected by the climate change events. The practices have now become important cultural practices. During the cultivation practice work division based on gender was also found significant. This documentation of traditional knowledge on cultivation practices would facilitate in the promotion as well as help to promote Kali Marshi as Geographical Indicator.

Acknowledgement

Authors are indebted to local farmers and government agencies for supporting during data collection.

References

- ADO. 2013. Agriculture development program and stastistics a glimps 2012/2013. Agriculture Development Office (ADO), Jumla, pp.183.

- Alteri, M, A. 2002. Agroecology: The science of natural resource management for poor farmers in marginal environments. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment. 93; 1-24.

- Aryal, S., Gaire, N. P., Pokhrel, N. R., Rana, P., Sharma, B., Kharal, D. K., Poudel, B. S., Dyola, N., Fan, Z. X., Grießinger, J. and Bräuning, A., 2020. Spring season in western Nepal Himalaya is not yet warming: a 400-year temperature reconstruction based on tree-ring widths of Himalayan Hemlock (Tsuga dumosa). Atmosphere, 11(2), p.132.

- CDD. 2015. Rice varietal mapping in Nepal: Implication for development and adaption. Crop Development Directorate (CDD), DoA, Hariharbhawan, Lalitpur.

- Chang, T. T. 1976. The origin, evolution, cultivation, dissemination, and diversification of Asian and African rices. Euphytica, 25(1), 425-441.

- Dhungel, S. 2017. Role of rice in food and nutritional security in Nepal Rice science and technology in Nepal. In: Poudel, M. N,. Bhandari, D.R, Khanal, M. P., Joshi, B.K., and Ghimire, K. H. (Eds.), Crop Development Directorate (CDD) Hariharbhawa and Agronomy Society of Nepal (ASoN), Khumaltar. pp 158-171.

- Dvkota, K., P. 2017. Use of oryza-3 simulation model for rice productivity Assessment in Terai District in Nepal: Rice science and technology in Nepal, eds. Poudel, M. N,. Bhandari, D.R, Khanal, M. P., Joshi, B.K., and Ghimire, K. H. 158-171. Crop Development Directorate (CDD) Hariharbhawa and Agronomy Society of Nepal (ASoN), Khumaltar.

- GoN and UNDP. 2014. Nepal Human Development Report 2014, Beyond Geography Unlocking Human Potential. Government of Nepal, Singha Durbar, Kathmandu and United Nations Development Program, Pulchowk, Kathmandu.

- GoN, 2014. National Population and Housing Census 2011 (Village Development Committee/Municipality). Government of Nepal, National Planning Commission Secretariat, Central Bureau of Statistics, Kathmandu, Nepal

- Joshi, B. K. 2005. Rice gene pool for Tarai and inner Tarai areas of Nepal. Nepal Agriculture Research Journal, 6, 24-27.

- Joshi, B. K. and Gauchan, D. 2020. Geographical indication. In: Joshi, B.K.; Gauchan, D.; Bhandari, B.; Jarvis, D. (Eds.), Good practices for agrobiodiversity management, Kathmandu (Nepal). NAGRC, LI-BIRD and Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, p. 35-39 ISBN: 978-92-9255-149-0

- Mallick, R, N. 1981. Rice in Nepal. Kala Prakashan, Kathmandu.

- MOALD, 2019, StatisticalInformation on Nepalese Agriculture, 2018/2019, Minister of Agriculture and Livestock, Government of Nepal.

- Newton, A. C., Akar, T., Baresel, J. P., Bebeli, P. J., Bettencourt, E., Bladenopoulos, K. V., Czembor, J. H., Fasoula, D. A., Katsiotis, A., Koutis, K. and Koutsika-Sotiriou, M., 2011. Cereal landraces for sustainable agriculture. Sustainable Agriculture Volume 2, 147-186.

- Ojha, P., Karki, R., and Subedi, U. 2020. Comparative Evaluation of Nutritional Value and Bioactive Components of Proso Millet, Foxtail Millet and Amaranth. In: Gauchan D., Joshi B. K., Bhandari B., Manandhar H. K. and Jarvis D. I. (Eds.), Traditional Crop Biodiversity for Mountain Food and Nutrition Security in Nepal. Tools and Research Results of the UNEP GEF Local Crop Project, Nepal. NAGRC, LI-BIRD and the Alliance of Biodiversity International and CIAT; Kathmandu, Nepal

- Palikhey, E., Sthapit, S. R., Gautam, S., Gauchan, D., Bhandari, B., Joshi, B, K., and Sthapit B., R. 2016. Integrating traditional crop genetic diversity into technology: Using a biodiversity portfolio approach to buffer against unpredictable environmental change in Nepal Himalayas. Baseline survey report, Hanku, Jumla: LI-BIRD, NARC and Biodiversity International.