Ria Fitriana†

Independent Consultant, Jakarta, Indonesia

Abstract

Gender recognition in fishery sector starts getting attention from many stakeholders. However, there are still uneven progress in accounting gender issues and mainstreaming gender in fishery sectors. Blue Swimming Crab fishery, as a case study, is one of main export commodities for Indonesia. Both gender, male and female, play a significant role along the value chain. Fishery improvement project, is a project designed to improve fisheries towards sustainability, is considered as an entry point to mainstream gender in fishery sector on the ground. The proposed interventions in Fishery Improvement Project of Blue swimming crab can be a tool to implement gender strategy and address gender inequalities.

Keywords

FIP, MSC, Gender, Blue Swimming Crab, Indonesia

1 Introduction

All fishery improvement projects (FIP), ultimately, work to achieve a level of performance consistent with an unconditional pass of the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) Fisheries Standard. MSC certification is an internationally standard in sustainable fishing and seafood products. FIP is a step process to get MSC certification which is a market driven process to ensure the sustainability of fisheries and governance. The demand for environmentally sound seafood increases, in parallel with the growing demand of socially responsible seafood. The recognition of human rights in certified seafood would be harnessing in combating human right violation including against any abuses and gender discrimination.

Blue Swimming Crab (BSC) Fishery in Indonesia is implementing FIP as a step to get MSC certification. Indonesia was the second largest producer of crab globally in 2014, with production reached 100,000 ton, valued at USD 313,000 (MMAF 2019). In 2018, volume of blue swimming crab contributed to 17% of total fish exported from Indonesia. Blue swimming crab fishing in Indonesia involves small scale fishery and larger industry at processing level. Stacey et al (2019) highlight both gender, male and female, play a significant role in small scale fishery. Therefore, female and male must share benefits and receive no impact due to intervention of Fishery Improvement Project (FIP).

The government of Indonesia has put noteworthy effort to mainstream gender in fishery sector. Several regulations and gender mainstreaming guidelines in fishery are provided at national level. Despite this greater awareness, moving beyond well-intentioned efforts in reducing gender disparity in fishery remains a critical challenge. Unclear picture still exists among stakeholders in fishery sector on how to integrate gender aspect in policy, program and project activities. FIP, where there are a wide range of activities from production, processing, fishery management and policy, is an opportunity to highlight ways to integrate gender aspect in fishery.

2 Method

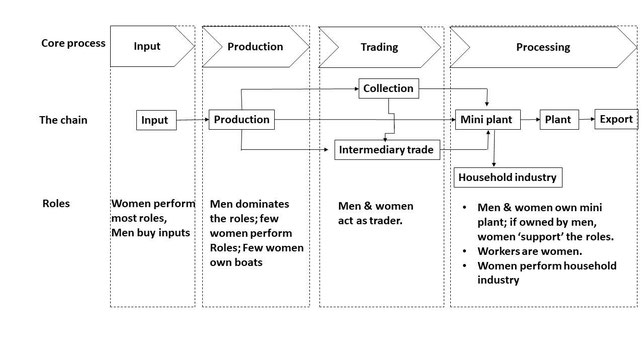

This study combines several approaches for gender analysis framework in FIP. The gender analysis follows every stage along the value chain. Value chain analysis is a method to analyse how the market works by identifying core processes, range of activities (e.g., production, processing and distribution) conducted by actors, their relationships and the values produced; those values are transferred along the chain to final consumers (Kaplinsky and Morris 2001, M4P 2008, Hempel 2010). There are several factors contributing to how the value chain works: 1) core process in the value chain, 2) activities conducted along the chain by actors, 3) key actors, 4) relationship among actors, competition between actors and concentration of power, 5) benefit sharing, and 6) assets and resources. The core process in the value chain involves input, production, trade, and wholesale and retail marketing. Then, activities in every stage of the core process were identified, along with the actors and relationships among actors, in order to determine gender relationships, disparities and differentiated impacts of inequalities along the value chain.

The results of gender analysis along the value chain was then applied to assess the interventions of FIP to explore the best practices of gender sensitive FIP. FIP, fishery improvement project, draws upon market forces, which include suppliers, retailers, food service providers, fishing industry actors, etc. The FIP identifies environmental issues that need to be addressed, sets the priority actions to be undertaken, and oversees implementation of the action plan (The Conservation Alliance for Seafood Solutions, 2015). There are three core principles (MSC 2018):

Principle 1 (P1): Sustainable target fish stocks. A fishery must be conducted in a manner that does not lead to overfishing or depletion of the exploited populations and, for those populations that are depleted, the fishery must be conducted in a manner that demonstrably leads to their recovery.

Principle 2 (P2): Environmental impact of fishing. Fishing operations should allow for the maintenance of the structure, productivity, function and diversity of the ecosystem (including habitat and associated dependent and ecologically related species) on which the fishery depends.

Principle 3 (P3): Effective management. The fishery is subject to an effective management system that respects local, national and international laws and standards and incorporates institutional and operational frameworks that require responsible, sustainable use of the resource.

The data collection combined a desk review of secondary data and primary data. The secondary data includes assessing publication, available reports from previous research and statistic. This study focuses on blue swimming crab in Madura Island, East Java Province, one of BSC production center in Indonesia. The primary data were based on interview with 69 people at input stage, fishers, traders, mini plant, association, government officers at village level, and University. The primary data were collected in Sumenep, Pamekasan and Bangkalan Districts, East Java in 2019. In depth interview was used for exploring gender issues. This method allows exploration and deeper discussion on gender concerns.

3 Results

3.1 Fishery improvement project of blue swimming crab

The fishery improvement project of blue swimming crab follows three core principles of MSC which are sustainable fish stock, minimizing environment impact and effective management. The FIP of BSC consists of 28 activities, cover all performance indicators in FIP (Table 1). There are six main activities under principle 1; 15 main activities in principle 2; and seven main activities in principle 3. Activities in principle 1 involve data management that contributes to harvest strategy and harvest control rule. In the FIP of BSC, all landed BSC must be recorded to measure stocks and then is used to calculate the harvest strategy and harvest control rules. Activities in principle 2 also involve data management and ecological aspect of crab, including secondary species, endangered, threatened and protected species (ETP), habitat and ecosystem. Activities in principle 3 are effective management that consists of exploring governance and national law and fishery specific management system.

Table 1: Main activities in FIP of BSC

| P1: Sustainability of Fish Stock | P2: Minimizing Environmental Impacts | P3: Effective Management |

|

|

|

3.2 Gender disaggregated roles along the BSC value chain

The discussion in this section follows value chain analysis of blue swimming crab. The core process in value chain includes input, production, trading, processing and retail marketing (Figure 1). The exploration of BSC in this study covers from input to mini plants in Madura. In East Java, there were 5,181 fishers, 81 mini plants and 2194 pickers (APRI 2019. Pickers are workers in mini plant whose task is to take the meat of crab out of its shell. The number of people in blue swimming crab industry would be more as input providers and traders at village level are not counted in this census. Almost 100% pickers were female based on the discussion with APRI in September 2019. Mini plant owners in Madura also described that all their pickers were female (St, Sk, October 2019).

This study found the most gears used in BSC fishery in Madura Island were nets and traps. Traps and nets were purchased for most of the cases. The fishers bought 3-4 sets of nets for example, 2 sets of nets were used while the rest were stored at home. Nets were bought but still needed to be adjusted with weights and floating stones. Nets had to be renewed weekly and broken nets were stored on the beach or burnt. There were several types of trap: iron, collapsible and bamboo traps. One fisher might have 150-200 traps. In one district fishers used iron traps while in other district fishers used bamboo traps and made by themselves. In trap fishing, bait was important aspect. The form of bait was sun dried fish where the fish were caught by other fishers and sundried by processors.

The discussion about BSC value chains starts at input stage (Figure 1). Female dominates at input stage by making the nets and traps. Male involves at input stage by preparing logistic of fishing trips. While male at sea, most female prepares all fishing equipment, nets and traps at home. This involves making and mending nets/traps, cleaning the nets and traps, and preparing baits. Female had to sit for more than 8 hours daily to knit the nets or constructing traps. The activities in preparing baits include re-sun drying fish, and insert baits into plastic bag to be used in trap fishing. The sundried fish itself was sold by female traders & processors. Female engages in more time consuming and manual tasks. This also shows that female plays significant roles at input stage.

At production stage, male dominates the work. Male operates the boats, sets the net and traps in the sea. Having caught crabs, the fisher unload the crab, bring to traders and sell it. We also found female involve at production stage by going to the sea as male counterpart. Female conducted fishing by themselves in several places in Talango Island, Sumenep, Pamekasan and Bangkalan Districts. Female also went for fishing with their male spouse/siblings. When female went to the sea, the activities were similar with male counterpart. We found female as the owner of vessels but did not go to the sea. In this role, the female boat owner provided all logistics and fishing equipment.

At trading stage, actors varied between male and female. The activities at trading stage started when a boat landed, the wives of fishers collected the crab and brought to weighting point. During low season, the male fisher brought directly to a trader. Thus, a trader received crabs, dripped water and weight them. A trader paid to those who brought the crabs, either male or female. Relationship between traders and fisher was unique. A trader had permanent clients or fishers who always sold to them. Even though a fisher did not have debt they still sold to a particular trader. This kind of relationship was built through trust, family kinship, and emotional bonding due to regular selling to a particular trader. New trader would be hard to enter, unless they provide good service to fishers and higher price

Thus, the crab was sold to mini plant owner at processing stage. The link is not necessary as a straight line (Figure 1). A fisher could also sell crabs to mini plant where mini plant owner cut the trader function. This depends on the dynamic relation between fishers, the nearest trader and mini plant. At processing stage, female conducted activities as owners, record, pickers and sorters. Females who work at mini plant as pickers were provided with tools and bench for picking the crab meat. These females had to wear working uniform and all equipment for food safety. The relationship between mini plant and traders was kinship relationship and business. By product from mini plant at processing stage, such as water from boiling crab, is utilized by food snack industry. The water from boiling crab is used to make crackers and condiment sauce ‘petis’. This home industry is mostly owned and conducted by female actors.

The gender disaggregated role shows high participation of female at input stage. Male and female conduct activities at production stage although number of female involves much less. Male dominates tasks at production stage, except for selling the catch and receiving payment. Both female and male involve at trading stage. Female dominates at processing stage. Looking at these actors’ roles, female and male engage in activities along the BCS fishery. Therefore, any intervention to improve BSC fishery must engage both actors.

Figure 1: value chain of blue swimming crab in Madura, Indonesia

4 Discussions

FIP is a step to get MSC Certificate. In this blue swimming crab (BSC) case, the intervention of FIP aims at meeting the MSC principles which is basically to achieve the sustainability of BSC fishing. FIP of BSC has a strong focus on biological and environmental aspects. Especially in Principle 1 and 2, the activities have a strong focus on biological aspect. Examining biological outcome is a key to evaluate the sustainability. This is not a surprising considering the aim of FIP to ensure sustainability of certain fisheries. However, managing a fishery is about managing people. The involvement of people is one of key successes in managing fisheries. Principle 1 and 2 lack of human focus, what is more gender aspect. Activities in P1 and P2 seem lack of involvement of main actors: fishers or traders. Refer to activities in FIP, data are collected by enumerators and discussed by scientists. No mention about gender of the enumerators. However, we found one female enumerator on site. This shows although the activities are gender blind but female still has opportunities to be enumerator.

In addition to that, the results of data collection (stocks and ecosystem) should be available for male and female fishers, traders and processor. Discussion about stock is about sea resource where male dominates at fishing as believed. In practices, both male and female engage to marine related activities and have interests. Female should know about harvest strategy. The most powerful actor along the value chain is actually the trader because of fishers’ dependency and bridging the fisher to market world. Information and management about stock would be strategic to work with traders, either male or female. Working with a female trader in Pamekasan, one site, is a good case where it has positive impact to her fisher clients.

Principle 3 discusses about governance, on how fisheries comply with relevant national laws and international agreements as well as fishery management system. This is an opportunity to empower fishers and primary key players on the ground to take role in the governance process. Decision making process should be accessible for male and female fishers, traders and processor. Exploring about regulation is considered as “big guy” work not fishers. On the other hand fishers and traders have to comply with the regulation. It is crucial to engage main actors in exploring regulation as it will impact to them as main actor on the ground. Activities in Principle 3 are opportunities to involve fishers & traders in the discussion about policy in fishery management.

Considering the gender disaggregated roles along the value chain of BSC, at least information about stock & ecosystem as well as intervention in FIP have to be disseminated to all key actors male and female. The involvement of all key actors along the value chain, female who works at input stage, male and female at production stage and traders will eventually contribute to the implementation FIP in achieving sustainable seafood.

Discussion about FIP should be available for all gender. It is essential to invite male and female in meeting for management establishment. The meeting committee needs to invite name of persons if number of female participants is expected to increase. It would be impossible for female to attend a meeting without their name on the invitation. Attending meeting is male or head of household’s work at local level. Female is likely not invited or contribute to exploring the policy and decision making process. In addition, time and venue also needs to enable female counterpart to attend the meeting. Therefore steering committee of meeting has to invite specifically and consider female’s time management.

In different case, discussion about BSC fishing was conducted through fishing association where no female as member. This situation makes female left behind on accessing information and improving capacity in general information. Improving the recognition of female as main actor in fishing organization will be strategic to encourage female’s participation due to lack of female participation in fishing group and discussion in public. No one should be left behind on the discussion about regulation.

FIP examination highlights about sustainability and compliance along supply chain. In fact FIP focuses more at production stage in the value chain of BSC. Pre-production tend to be ignored in the discussion. Indeed, bait is important for trap fishing. Addressing bait issue would help decreasing females’ burden in supporting crab fishing. A long hour work (more than 8 hours/ day and almost every day) would have significant impact to fatigue stiff muscles and eyes concern to female. No one force female spouse to work in a long hours. Due to aiming at going to the sea daily and catching more crab, then female spouse has to provide fishing equipment as much as they can.

In addition, the load to support their spouse as fishers tend to be ignored and not protected by the labor law, contrarily with labor in larger scale industries that is protected by the labor law. The importance of their contribution to BSC fishing needs to be acknowledged as the first step. Then intervention to improve the working environment and health concern of female spouse in making fishing equipment could be addressed respectively.

The interventions in the FIP of BSC are more focus at production stages to result sustainable crab fishing. This might lead to miss overall sustainability issue and intervention for sustainable fishing might have impact to female’s burden. Lack of gender recognition in understanding key stakeholders and labor practices creates gender disparity. The debate about sustainable concern is deeply rooted in food ethics. The sustainable values have to consider environmental and social concerns, engages in a range of ethical values include protecting the environment as well as ensuring economic well-being, providing fair access and equal benefit for all key stakeholders, male and female. Recognition of female counterpart as key actors in crab industry as well as paying careful attention towards the invisible support of female counterpart at input and production stage contributes to discussion about the ethics of the current state of food system.

The assessment process of socio economic monitoring in MSC/FIP is an opportunity to incorporate gender concerns in FIP. At the moment, the socio economic has no gender aspect. Socio economic monitoring could benefit gender analysis and contribute to gender sensitive and responsive activities in FIP. Therefore, monitoring of social impact is a key to ensure no gender disparity in FIP.

After all, long term goal of mainstreaming gender in FIP is to have MSC as market driven for seafood certification that ensure environmentally and socially responsible seafood products. The growing awareness about ethical food is an opportunity to incorporate gender perspective in the FIP/MSC. The objective is to have gender sensitive and responsive FIP. This could be done by:

1. Gender segregated data on the actors along the value chain and contribution of each actors by gender.

2. Gender concern is incorporated in socio economic assessment as part of MSC (FIP) process

3. Gender issues addressed adequately in process, plans, and implementing actions of FIP.

5 Conclusion

FIP is a step process to get MSC certification which is a market driven process to ensure the sustainability of fisheries and governance. This is an opportunity to enhance fishers and primary key players on the ground to be part of the governance process. Improve understanding on heterogeneity of key players on the ground will improve understanding on the socio economic impact and drivers of actions, including gender concern. Fishery Improvement Project (FIP), as one way to address the sustainability issue of fishery must also be enjoyed by both male and female. Gender mainstreaming in FIP is meant to be a strategy for promoting empowerment of female to ensure that male and female in BSC fisheries benefit equal rights and opportunities. This is particularly relevant to ethical food production. FIP, within the MSC certification process is expected to ensure the ecologically sustainability and make change in more socially responsible seafood initiative.

Acknowledgement

This study was funded by United Nations Development Programme through the Global Sustainable Supply Chains for Marine Commodities Project (GMC) project. The contents in this paper are solely responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNDP or GMC project.

References

- APRI (2019). Indonesia Blue swimming Crab Fishery Improvement Program, September 2019.

- Conservation Alliance for Seafood Solutions (2015). Guidelines for Supporting Fishery Improvement Projects.

- Hempel, E. (2010). Value Chain Analysis in the Fisheries Sector in Africa. INFOSA.

- Kaplinsky, R., and Morris, M. (2001). A handbook for value chain research. Report prepared for IDRC.

- MMAF (2019) Indonesia adalah Surga Perikanan Dunia, Infografik.

- Making Market Systems Work Better for the Poor/M4P (2008). Making Value Chains Work Better for the Poor: A Tool book for Practitioners of Value Chain Analysis. DFID.

- MSC (2018). MSC Fisheries Standard Version 2.01, 31 August 2018. Marine Stewardship Council.

- Stacey, N., E. Gibson., N. Loneragan., C. Warren, R. Fitriana, B Wiryawan, D. Adhuri (2019). Enhancing Coastal Livelihoods in Indonesia: an evaluation of recent initiatives on Gender, women, and livelihoods in small scale fisheries, Maritime Studies: 142. Special Issues.